Key messages

- A flexible step-by-step process that supports continuous learning, adaptation and responsiveness.

- Programming works with the system and embeds people’s rights, needs, perspectives and experiences at every stage of design and implementation.

- It strengthens the relationship between people and service providers, building trust, agency and accountability.

- Reflection, iteration and adjustment are core practices in justice and security programming.

3.1 A snapshot of the three-step process

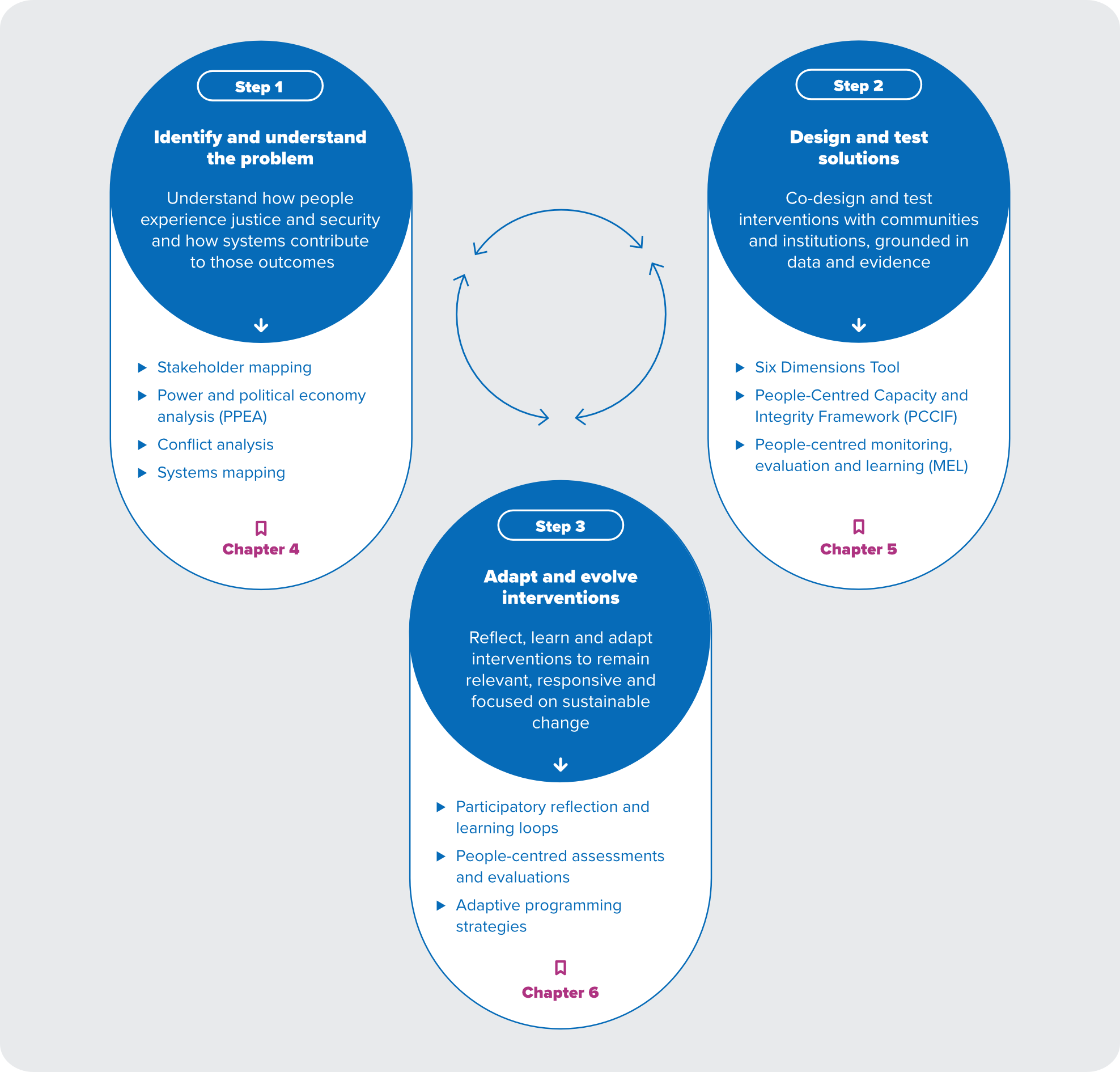

The three-step process for designing and implementing the people-centred approach is practical, grounded in the UNDP people-centred policy framework, and supports UNDP teams to move from policy to action in a way that is adaptive, inclusive, and responsive to local realities.

The process is structured around three steps that mirror the three phases of the UNDP programme cycle (design, implement and transition) and are shown in Diagram 3:

| Step 1 | Identify and understand the problemUnderstand how people experience justice and security and how systems contribute to those outcomes. |

| Step 2 | Design and test solutions Co-design and test interventions with communities and institutions, grounded in data and evidence. |

| Step 3 | Adapt and evolve interventions Reflect, learn and adapt interventions to remain relevant, responsive and focused on sustainable change. |

The process is designed to be flexible and iterative, rather than linear. The three steps are interconnected functions that continually shape and inform one another, supported by robust monitoring, learning and evaluation, as shown in Diagram 3. Teams will move between these steps as new information, opportunities and challenges emerge. This iterative process is essential to people-centred and systems-informed programming.

As teams will discover:

- Insights from Step 1 (such as system dynamics, people’s experiences and power relationships) inform how interventions are designed in Step 2: who co-designs, which constraints must be considered, and what resistance or risks should be anticipated.

- Testing in Step 2 often reveals new dynamics or hidden assumptions, prompting teams to revisit their analysis in Step 1 and refine their understanding of the system.

- Learning in Step 3 builds on Step 2, revealing whether interventions are shifting trust, legitimacy or outcomes for people, and informing what requires adaptation, refinement or return to design.

- Adaptation or scaling decisions in Step 3 often require a fresh look at system conditions and deeper context analysis under Step 1, sometimes surfacing entirely new entry points for change.

Each step includes tools, examples, programming tips, reflection questions and common pitfalls to avoid for people-centred programming.

The steps are supported by a set of core design principles detailed in the following section. Where the steps are about doing, the design principles shape how to implement each step in accordance with the people-centred approach.

Diagram 3: The three-step process and key programming tools

3.2 Seven design principles for programming

Seven core design principles underpin people-centred justice and security programming. These principles translate the values and vision of the UNDP people-centred policy framework into practical guidance for how interventions, projects and programmes are designed, implemented and adapted (see Table 5).

The seven principles shape every aspect of design, delivery and impact. They help teams embed the people-centred approach from the outset and sustain it throughout implementation, adaptation and scaling. Interdependent and mutually reinforcing, the principles apply at all stages of the programming cycle and should be revisited regularly as programming evolves.

Start with people’s justice and security needs

People’s needs include their legal and human rights and their ability to access to fair, accountable services and just outcomes. Understandings of justice and security problems must be shaped by people’s actual experiences. Start by listening to how people, especially women, youth and other marginalized groups, experience injustice and insecurity in their daily lives, and ensure that their voices are central in defining the problems to be addressed.

Design with people, not for them

People-centred programming means designing and testing solutions with the people most affected by justice and security problems. Engage communities as active partners with government and State institutions and with informal mechanisms and actors in shaping priorities, co-creating solutions and defining what success looks like.

Work with the ecosystem

People-centred programming means designing and testing solutions with the people most affected by justice and security problems. Engage communities as active partners with government and State institutions and with informal mechanisms and actors in shaping priorities, co-creating solutions and defining what success looks like.

Focus on relationships, not just institutions

The people-centred approach prioritizes rebuilding trust-based relationship between justice and security institutions and the people they serve. Trust and legitimacy grow when institutions and their personnel are able to deliver accessible, accountable, fair and quality services that respond to people’s rights, needs and expectations

Strengthen people’s agency and voice

People-centred programming strengthens people’s ability to influence and take part in the decisions that shape their access to justice, safety and rights. Agency means that people and communities are not passive recipients of support but active drivers of change. This involves building their knowledge, confidence and collective voice to claim rights, solve problems and hold State, non-State and hybrid justice and security actors to account.

Measure what matters to people

Programming success should be judged by the quality of the relationship between people and justice and security providers (State, non-State and hybrid), not just by institutional outputs. This means tracking whether people experience these providers as fair, accountable, responsive, inclusive and trustworthy, using evidence from people’s everyday experiences and perspectives alongside institutional data.

Adapt as you go

Justice and security challenges are complex and context-specific. There are no one-size-fits-all solutions. Addressing them requires creativity, testing, learning and adaptation. Use regular reflection, feedback, and evidence to refine, adapt, and scale interventions based on what works for people in a given context.